|

Click to listen to this article

|

By Daniel A. Sumner, Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of California, Davis

The quantity of carrots available to U.S. consumers has not changed much since the beginning of the 21st century 25 years ago. In 2000, domestic availability of fresh carrots (production plus imports minus exports) was about 2.6 million pounds. And in 2023, availability was about 2.85 million pounds before falling to 2.5 million pounds in 2024.

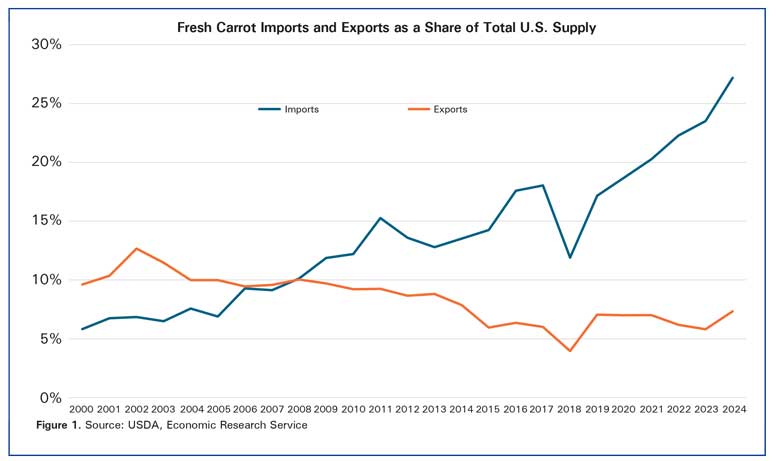

The substantial change in fresh carrot availability is shown in Fig. 1, where we see that imports have grown from a little less than 6% of U.S. supply to more than 27%. Meanwhile, exports of fresh carrots fell from about 10% to about 7% of U.S. supply. U.S. production was more than 25% higher 25 years ago when imports were only a quarter of what they have been recently. Exports have fallen gradually by about one third.

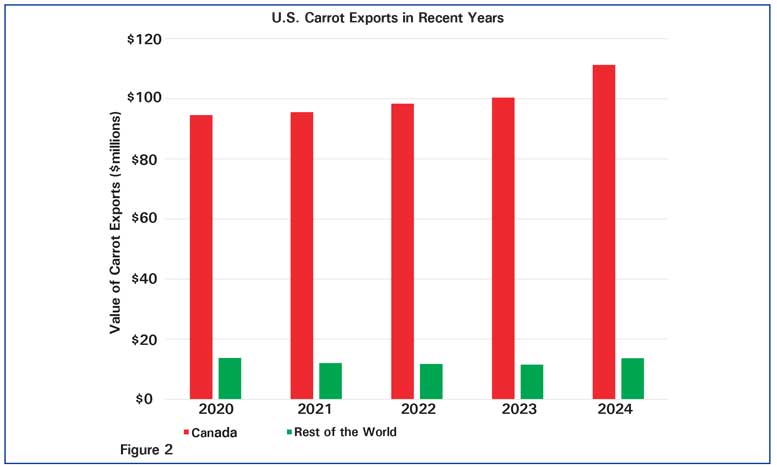

The United States has long been a significant exporter of carrots. Almost all are fresh carrots, and about 90% are shipped to Canada. U.S. exports of fresh carrots are now about the same quantity as were U.S. imports 25 years ago, and most are shipped in the winter and spring when Canadian fresh carrots are less available. Recent data on U.S. carrot exports by destination are shown in Fig. 2.

U.S. imports of carrots have become far larger than exports, and the import pattern is more complex. While most imports are of fresh carrots, processed carrots (mostly dried, frozen and preserved) comprise about 13% by volume and twice that share by value of imports. The idea that the U.S. imports primarily processed carrots is simply wrong. The U.S. market share of U.S. produced carrots has declined in both fresh and processed carrots.

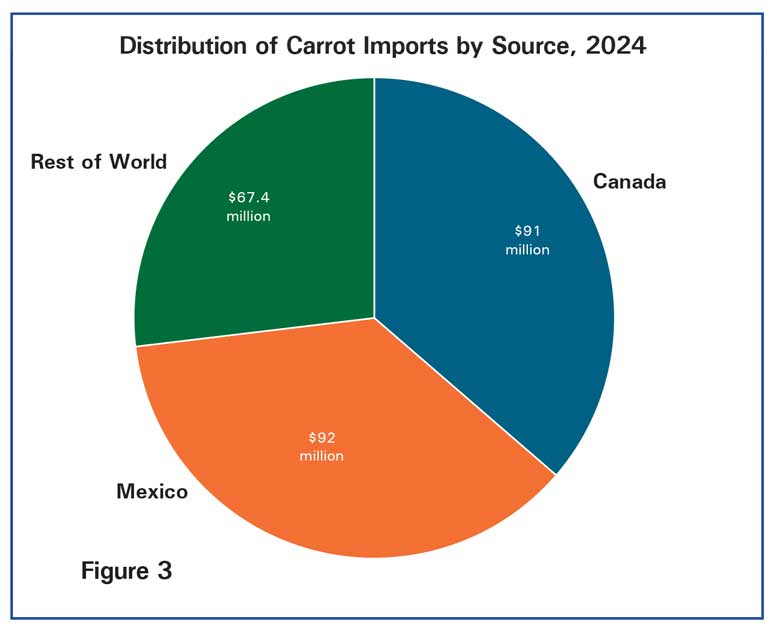

Fig. 3 shows that the value of U.S. imports in 2024 totaled about $250 million. These imports were divided three ways: about 36.5% each from Mexico and Canada and about 27% from the rest of the world. Almost all the fresh carrots are from Canada and Mexico, and more than one third of the processed carrot imports are from other sources including China for about half the dried carrots, which comprises only about 5% of total carrot imports.

Carrot imports are relatively rare among horticultural crop imports with substantial shipments from both Mexico and Canada. With most of the U.S. carrot production in California, one might expect Mexico might be a seasonal exporter of carrots to the United States during periods when California carrots are not in the market. This picture of the market does not fit the facts. California production is not overly seasonal, carrots are storable, and Canada is also a major shipper of fresh and processed carrots.

These trade issues have come into focus in 2025 as the U.S. government has highlighted products for which the U.S. is a net importer. Some have pointed to production of goods for which the United States is well suited. A question for carrot trade is why has U.S. carrot production not kept pace with domestic demand. For example, what advantage does the Canadian carrot industry have over the northern tier states including Wisconsin and Michigan for both processed and fresh carrot supply? For California, one question is why has carrot production stagnated, allowing a large expansion of imports. Carrot acreage in California did not displace field crops in the way that almond and pistachio acreage did. Is that because carrots are already covering the most suitable land or are there other economic rather than mostly agronomic factors in play?

As trade policy pressure continues in one form or another, it is important that the U.S. carrot industry observers and participants consider options for expansion to displace imports if barriers or import tariffs make relying on our neighbors for supply less feasible. This pressure emphasizes the vital importance of research and development for productivity growth and for creating carrot products that suit the demands of modern consumers.