|

Click to listen to this article

|

By Umbrin Ilyas and Mary Ruth McDonald, University of Guelph

Evaluating certain characteristics of soil may help predict the risk of cavity spot in carrots and, in turn, allow growers to make decisions to manage the risk, according to recent research at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada.

Cavity spot is a soil-borne disease of carrots that occurs in many carrot-growing regions around the world. The disease causes shallow, sunken and horizontally shaped lesions on carrot roots (Fig. 1). These symptoms lead to economic losses for growers. The disease usually starts to appear when carrot roots start to expand (mid-August in the Northeast), and lesions increase in size until harvest. No symptoms are visible above ground. Carrots must be pulled and sometimes washed before the symptoms are apparent (Fig. 2).

Cavity spot has been reported from most commercial fields growing carrots on high organic matter soil in the Holland Marsh, Ontario, Canada. The Holland Marsh is the largest carrot-producing region in Ontario, accounting for 62% of the province’s carrot production.

Cavity spot is an unusual disease because it is caused by several species of the “water molds” Pythium and Globisporangium that naturally occur in the soil. The disease tends to be more severe in seasons with higher total rainfall or heavy irrigation, especially when there is increased rainfall in the two or three months before harvest (August and September in the Northeast).

No commercial carrot cultivars are fully resistant to cavity spot. Management options are limited and include using raised beds to reduce soil moisture, rotating crops for three to six years and applying one of the three fungicides currently registered in Ontario. Despite these efforts, cavity spot continues to appear in commercial fields in the Holland Marsh.

A recent study focused on developing a soil test to assess the risk of cavity spot in a field before seeding. This would allow growers to make informed decisions such as avoiding high-risk fields or choosing less susceptible cultivars if available.

Soil Sampling Strategy for Cavity Spot Risk Assessment

Soil samples were collected just before seeding from 22 commercial carrot fields in the Holland Marsh. Fields with a known history of cavity spot were selected in collaboration with the local integrated pest management team using field data from 2015 to 2019. All selected fields were located within a 20-km radius, had muck soil with 35–80% organic matter, followed an onion–carrot rotation and used similar agronomic practices. Each field was seeded with orange carrot cultivars.

In each field, four sites measuring 10 x 10 meters (11 x 11 yards) were selected and marked using GPS. These sites were spaced 50 to 100 meters apart. At each site, approximately 10 soil cores were collected in a W-pattern using a soil sampler to a depth of 20 cm (Fig. 3). Samples were sent to laboratories for soil nutrient analysis and microbial identification.

In early October, carrots were harvested from the same GPS-marked sites to assess cavity spot severity. Fields with disease severity between 5% and 10% were classified as low-risk, while fields with severity between 15% and 45% were considered high-risk.

Key Findings

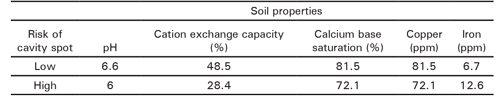

The study identified several differences in soil properties and microbial communities between low-risk and high-risk fields for cavity spot. Low-risk soils had higher calcium base saturation (CaBS) at 81.5%, higher cation exchange capacity (CEC) at 48.5 meq/100g and a pH of 6.6. In contrast, high-risk soils had higher levels of copper (Cu) at 12.6 ppm and iron (Fe) at 209.6 ppm and lower pH (~6) (Table 1).

Microbial analysis also showed differences between risk categories. Low-risk soils had greater abundance of some kinds of fungi such as Mortierella, Emericellopsis and some bacteria such as Rubellimicrobium. High-risk soils had higher populations of known pathogens including Globisporangium, Pythium and some kinds of fungi such as Fusarium, Fusicolla, Mrakia, Penicillium and bacteria like Bradyrhizobium and Staphylococcus.

Recommendations

These results suggest that the risk of cavity spot can be assessed before seeding carrots based on specific soil chemical characteristics and microbial taxa. In the Holland Marsh, carrot growers using an onion–carrot rotation are advised to consider a field high-risk for cavity spot if soil copper is ≥ 12 ppm and iron is ≥ 210 ppm. Fields are more likely to be low-risk when soil pH is ≥ 6.6 and calcium base saturation is ≥ 80%.

Further validation is needed to confirm these indicators. This work was done only on high organic matter soils, and it is not known if the same factors will be important on mineral soils. Expanding research to other regions and soil types will help determine whether these predictors are broadly applicable for managing cavity spot risk. We are sampling more carrots field this year, and the research is continuing.

Details of the trials can also be found on the research station website at bradford-crops.uoguelph.ca.