The Cost of Beet Leafhoppers in Columbia Basin Carrot Crops

By Gina Greenway, Greenway Research

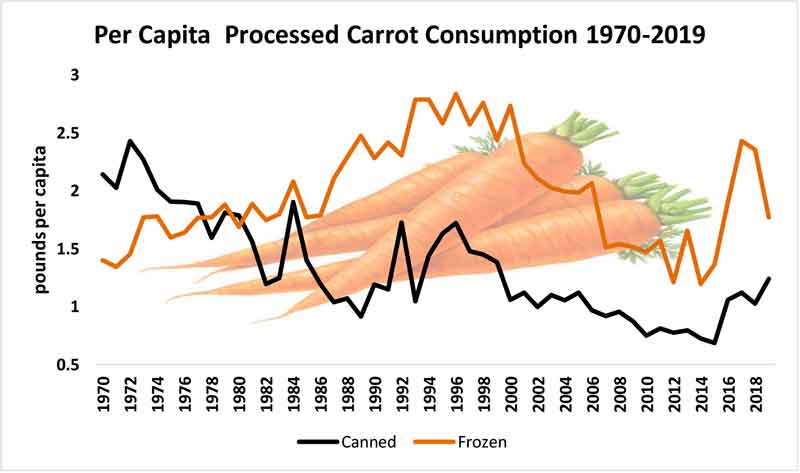

The COVID-19 pandemic has shifted America’s eating habits. It’s hard to predict if any of the changes in consumption patterns will be sustained long term, but for now a lot of folks are cooking more, spending more time at home and shopping less frequently. With fewer trips to the grocery store, frozen and canned vegetables may be substituted for fresh more often than in the past. I don’t know if consumers will eat more frozen and canned carrots in 2020 and 2021, but it’s interesting to think about.

According to the USDA, frozen carrot consumption has ranged from a low of 1.19 pounds per capita to a high of 2.83 pounds per capita in the last 49 years. Canned carrot consumption peaked back in 1972 at 2.42 pounds per capita, but looks to be trending upward since reaching a low of 0.68 pounds per capita in 2015.

Maybe 2020 and 2021 will look like 1996 when consumption of both frozen and canned carrots was high. But even if consumption hovers around the average, the job of providing the processed market with a stable supply of high quality raw product remains an important one met with a variety of challenges.

One of the most unpredictable and costly challenges impacting carrot and other vegetable and vegetable seed crops is pest pressure. I am always trying to learn more about the economic impacts of sucking insects, their interactions in vegetable crops and how the research community can provide tools to help make managing these pests less costly. One of the first steps has been to establish economic benchmarks for key pests in different crops.

Surveying the Field

To gain insight into the impacts of beet leafhoppers in carrot crops grown for processing in the Columbia Basin, I conducted an expert opinion survey of growers and consultants in the region. I hoped to better pinpoint the number of beet leafhopper targeted applications typically made per season and to identify which products are used most often to manage the pest. I also wanted to gain a better understanding of the impact of beet leafhopper transmitted diseases on yield.

Results of the survey highlighted esfenvalerate, cyfluthrin, imidacloprid, thiamethoxam and methomyl as key active ingredients used for beet leafhopper management.

After determining which active ingredients to focus on, the next step was to get a better idea of the frequency of use. To do this, I asked participants to estimate the number of beet leafhopper targeted spray applications typically made per season. About 20 percent of folks who responded reported making one beet leafhopper targeted spray application per season. Another 20 percent of respondents reported typically making two beet leafhopper targeted spray applications per season. An estimated 60 percent of survey participants reported making three beet leafhopper targeted spray applications in a typical growing season.

The frustrating thing about pests like leafhoppers is their ability to raise the cost of production and damage revenue at the same time. To better quantify the impact of leafhoppers on revenue, I asked survey participants to estimate how much yield would increase if beet leafhoppers did not exist. Responses ranged from 1 percent to 15 percent.

I also wanted to try to gain insight into perceptions of leafhopper mitigation strategies. I asked participants to estimate the percentage increase in yield that could be achieved if they were able to improve the execution and timing of beet leafhopper targeted insecticide applications. Results ranged from 0 percent to 10 percent.

Estimating the Expense

To arrive at dollar value estimates of the cost of beet leafhoppers in carrots grown for processing, results of the survey were combined with pesticide label information, pesticide pricing information, and planted acreage, price and yield estimates reported by the USDA. Application costs were omitted based on the assumption that the majority of beet leafhopper targeted applications would be tank mixed.

The overall costs of insecticides were estimated to range from about $3.50 per acre to $32 per acre but will depend on application rate, product choice, environmental factors, individual preference and pressure from other pests. Yield was assumed to be 38 tons per acre, planted acreage was estimated to be 6,100 and price was estimated to be $84 per ton.

Expenditures on beet leafhopper targeted insecticide applications were estimated to range from about $154,000 to $220,000, depending on product choice and pressure. Estimates of the value of lost yield attributed to beet leafhopper transmitted diseases will likely be a little bit different for everyone, as was indicated by the variation in survey estimates. It would be difficult to quantify how much yield is lost with a high level of precision, but considering how much different scenarios of yield loss could cost the industry is worth thinking about. If 20 percent of acres planted are impacted by a 15 percent reduction in yield because of beet leafhopper transmitted disease, the foregone value rings in at $584,000. If 60 percent of planted acres experience a 7 percent yield loss, the forgone value would be about $817,000.

The next logical step is to consider what can be done to reduce yield losses. One key tool is better information for improved decision making. Many survey participants believed proper timing and execution of insecticide applications could improve yield. If half of all growers in the region were able to increase yield by 5 percent as a result of the ability to make better decisions regarding timing and execution of insecticide applications, the benefit to the industry would be just under half a million dollars. Coordinating and expanding pest monitoring efforts in multiple vegetable and vegetable seed crops can help growers make proactive and effective management decisions, helping to reduce the costs of pests in the Columbia Basin.