By Sam Hitchcock Tilton, Daniel Brainard, Chun-Lung Lee, Department of Horticulture, Michigan State University

Production of organic carrots is challenging, due in part to the difficulty of managing weeds. Preventive measures that reduce the weed seedbank – such as crop rotation, fallow periods and stale seedbeds – are helpful, but often growers rely on mechanical cultivation and expensive hand-weeding to control weeds.

At Michigan State University (MSU), we are evaluating “in-row” mechanical cultivation tools in carrots aimed at reducing hand-weeding costs and yield losses due to weeds. In addition, we are exploring the potential for “cultivation-tolerant” varieties to further improve weed management in carrots.

In-Row Mechanical Cultivation

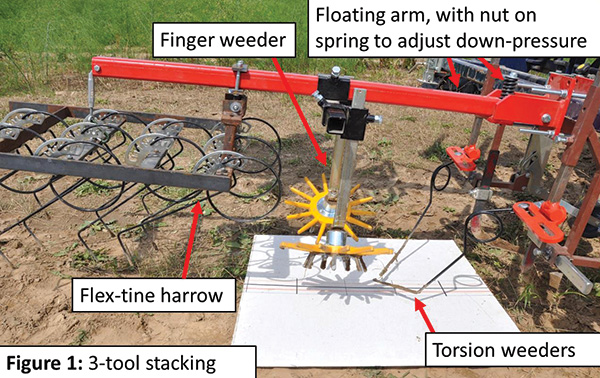

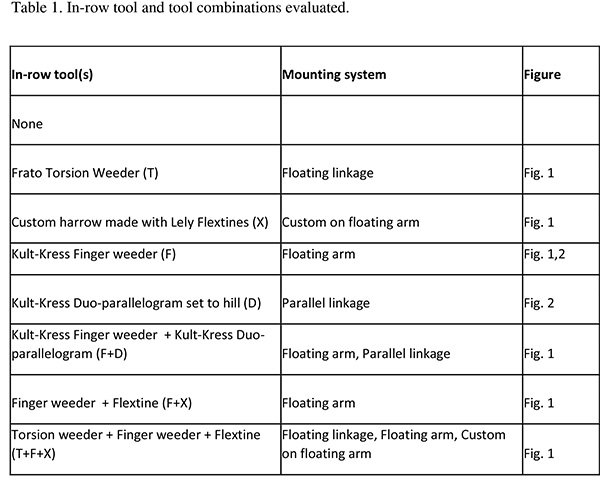

Cultivating weeds between crop rows is relatively easy using a wide range of tools including sweeps, knives, rolling cultivators or cutaway disks. With either camera guidance systems or hand-steered toolbars guiding the cultivator, in-row weeds can be limited to a narrow band of about 2 inches (Fig. 3). Management of weeds in this narrow “in-row” band is far more challenging due to the risk of damaging the crop. Nevertheless, several tools are available that can help. We evaluated several tools (Table 1, Fig. 1, Fig. 2) including finger weeders, torsion weeders, flex-tine cultivators and mini hilling disks. These can be used alone or “stacked” in various combinations to improve their efficacy.

These tools work primarily by uprooting or burying weeds. To work effectively in the crop row without injuring carrots, the carrots must be more resistant to uprooting or burial than the weeds. In short, the carrots need to have a size advantage over the weeds in either root length (for tools that uproot) or height (for tools that bury). This means managing weeds early and often, ideally when they are in the “white thread” or cotyledon stage, so that weeds are as small as possible.

In our trials, we flame-weed just before carrots emerge. As soon as carrots have emerged, we use cutaway disks to remove weeds as close as possible to the crop row. If flame-weeding is timed appropriately (just before carrot emergence), the density of weeds can be greatly reduced. Missing this window of opportunity can result in a drastic increase in weeds emerging with the carrots (Fig. 4).

Tool Testing Methods

Bolero carrots were planted on a flat, sandy field at the MSU Horticulture Teaching Research and Extension farm. The same trial was repeated three times during the summer of 2017. We evaluated the effects of all tools on naturally emerging weeds, as well as weeds that we sowed in order to obtain more consistent stands for evaluation. These “surrogate weeds” included a representative broadleaf (yellow mustard) and grass (Japanese millet) species that were sown in the crop row following flame-weeding and carrot emergence.

At the time of applying the cultivation tools, carrots were in the one- to three-leaf stage, and weeds were in the cotyledon to one-leaf stage. We counted weeds and carrots before and after cultivation to evaluate the survival of both. After using the tools, we also recorded the time required to hand-weed each plot and evaluated carrot yield and quality.

Figure 4. Propane flame-weeder applied pre-emergence to the row on the left but accidently shut off over the row on the right, resulting in a perfect opportunity to show the effect of pre-emergence flame-weeding.

Effects of Tools

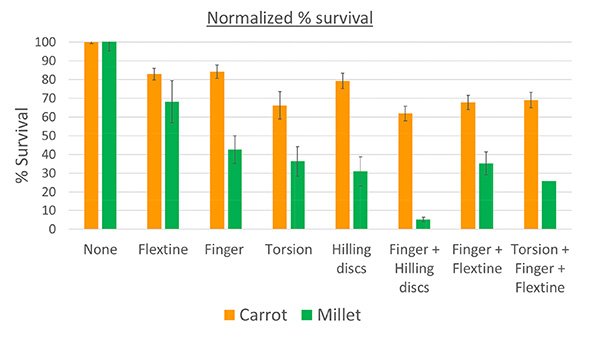

Tool-inflicted destruction to weeds ranged from about 30 percent with the flex-tine cultivator to 95 percent with the finger + hilling disk (Fig. 5). Stacked tool combinations often had higher efficacy than those tools used individually. All tools reduced hand-weeding time by approximately 25-100 hours per acre compared to the control, where cultivation tools were only applied between rows.

At the same time, carrot mortality ranged from 15 percent to 40 percent in response to these in-row tools. Although this may seem like unacceptable stand loss to some growers, note that carrot planting densities can be bumped up to compensate. Increasing carrot populations requires extra seed costs, but these are dwarfed by the labor savings. At our relatively high seeding rates of 30 seeds per foot, we did not detect significant differences in carrot yields or quality between the tools, although clearly stand reductions could result in yield losses if initial densities were too low.

Cultivation-Tolerant Cultivars

Another approach to improving weed management in carrots is to select cultivars that are resistant to the physical forces applied by cultivation tools. This would allow growers to run tools more aggressively and kill more weeds with reduced risk of stand loss.

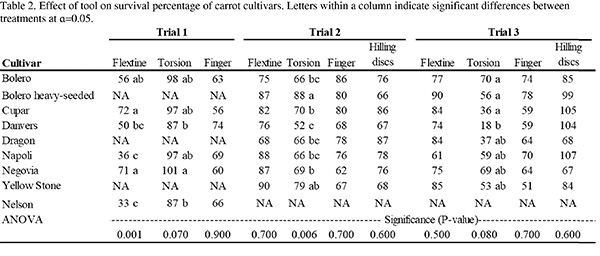

To test this idea, we planted eight commercially available carrot cultivars in replicated plots, ran several individual tools over them and evaluated survival. Noting that the size of carrot seeds within each cultivar sometimes varied a lot, we also sieved seeds of one cultivar (Bolero) to obtain just the largest fraction, and separately evaluated its tolerance to the tools. We hypothesized that larger seeds would result in larger plants with greater tolerance.

We repeated this trial once in 2016 and twice in the summer of 2017. Carrots were managed as previously described, with pre-emergence flame weeding and near-row cultivation with a cutaway disk.

Results were mixed (Table 2). For finger weeders, we did not detect any clear differences in cultivar response. However, for flex-tine cultivation (trial 1) and the torsion weeder (all trials), cultivars varied in their tolerance. For example, for the torsion weeder, Danvers stood out as a relatively susceptible cultivar, while Bolero was relatively tolerant. In trial 2, the larger fraction of Bolero seeds also resulted in greater tolerance. These results suggest that growers can improve weed management by choosing existing cultivars that are resilient to cultivation tools.

Greater understanding of the traits associated with this cultivation-tolerance may guide carrot breeding programs to improve the performance of their varieties in mechanically cultivated systems by selecting for and amplifying those traits that make a carrot resistant to cultivation. Of course, carrot growers choose varieties based on many characteristics, and the tradeoffs associated with cultivation tolerance must be considered. But given the challenge of managing weeds, we believe this approach has potential to improve grower success with organic carrot production.