Certis Biologicals has launched its new copper product Kocide 50DF (copper hydroxide) for specialty crops in all states. The high-load copper bio-fungicide is designed to serve as both a preventative and curative product to combat a variety of fungal plant diseases, including Alternaria leaf spot and Cercospora leaf spot in carrots.

The new Kocide 50DF formulation mixes with low dust residue, is easy to pour and disperses into the mix solution quickly, producing even coverage during application, according to the company. The product can be applied through foliar, aerial spray, sprinkler chemigation or ground boom application methods.

Visit www.certisbio.com.

Author: Brian

-

Certis Expands Copper Product Lineup

-

Snack Foods Company Introduces BBQ Carrot Crisps

Snack foods company Dirt Kitchen Snacks has added Air-Dried Carrot Crisps with Smoky Barbeque Seasoning to its portfolio of products. The snack, which the company bills as a new veggie-based twist on BBQ potato chips, is made from crispy, crunchy air-dried carrots tossed in extra virgin olive oil and a bold, smoky barbeque seasoning. The new product contains 35 calories per serving and is vegan, non-GMO, gluten-free and kosher. The carrot crisps contain no artificial flavors, colors, preservatives or added sugar.

Dirt Kitchen Snacks, a business launched in 2020, also sells a carrot and apricot pressed bar. The carrot snacks are available online at www.dirtkitchensnacks.com.

-

McCain Foods Acquires Dutch Frozen Foods Company

McCain Foods has acquired Scelta Products, a Netherlands-based producer of frozen foods. This purchase is the latest in a series of investments and acquisitions McCain has made in recent years to expand its appetizer and snack offerings.

Scelta Products has been in the frozen vegetable industry for more than 22 years and has been a business partner of McCain’s for 13 years. Scelta Products’ vegetable appetizers fit well within McCain’s existing appetizers portfolio and will allow McCain to serve growing customer demand for snacking options, according to the company.

-

Making Progress

Photos courtesy USDA-ARS

Mello Yello from Bejo Seeds was among the 40 novel carrot hybrids in the trial. Carrot breeders appear to be making some progress in their work to breed nematode-resistant carrots. Carrots with nematode resistance were among the promising results of the 2022 USDA-ARS Hybrid Carrot Trial. Specifically, a few carrot hybrids that have nematode resistance, such as numbered lines C2145 and C208, did well in the cello category of the trial. Breeding nematode-resistant carrots is an ongoing goal of the USDA-ARS carrot research program in Madison, Wisconsin.

This entry from Pop Vriend was one of the 40 cultivars in the baby carrot category. Carrots grown in the trial were on display and evaluated in late September at the University of Wisconsin campus in Madison. Entries included 40 baby, 35 cello and 40 novel carrot hybrids from various seed companies and the USDA cooperative breeding program.

This entry, C208, is a carrot hybrid with nematode resistance that did well in the cello category of the trial. The trial was grown on sand at Paul Miller Farms near the University of Wisconsin Hancock Research Station. In general, the growing conditions were typical for the area with the exception of a cold, wet spring. There was also a heavy rain shortly after planting that caused the loss of a few plots.

-

Tessenderlo Kerley Inc. Breaks Ground for Ohio Fertilizer Facility

Tessenderlo Kerley Inc. held a celebratory groundbreaking to mark the commencement of construction on a new liquid fertilizer facility in Defiance, Ohio. The 50,000-square-foot production facility will occupy 50 acres and is set to become operational in 2024. The facility will serve the eastern Great Lakes region through its distribution partners and will include terminal load-outs for railcars and tanker trucks.

Tessenderlo Kerley will produce its liquid sulfur-based crop nutrition brands such as Thio-Sul, KTS and K-Row 23, as well as sulfite chemistries for the industrial market.

-

International Flavor

Story and photos by Denise Keller, Editor

After a two-year postponement, the 40th International Carrot Conference gave nearly 100 attendees from nine countries a look at the latest research and issues impacting the carrot industry.

The conference, held Aug. 29-30 in Mount Vernon, Washington, hosted university researchers and grad students, as well as seed company reps, breeders and a handful of growers. Attendance was lower than organizers had hoped, with the smaller turnout attributed to lingering concerns of international travel in the COVID era, as well as the meeting location. Participants of the 2018 International Carrot Conference, held in Wisconsin, voted to have the 2020 conference (which was rescheduled for 2022) in Western Washington despite the absence of any major carrot production in the area. This likely limited grower attendance, said Lindsey du Toit, conference organizing committee chair and Washington State University (WSU) vegetable seed pathologist.

For those who made the trip – with attendees hailing from the U.S., Canada, Brazil, Peru, France, the Netherlands, Italy, New Zealand and Japan – day one provided an overview of research being done on carrots in the U.S. Carrot breeders shared what traits they are selecting for, reporting on progress in breeding for resistance to nematodes and diseases such as cavity spot and bacterial leaf blight. They also discussed efforts to breed for traits such as fast-growing tops so carrots can better compete with weeds, especially important in organic production.

Ellie Janda and Leeza Regensburger with the Organic Seed Alliance check out the rainbow carrot population Fantasia. Conference Keynote

Roger Freeman, a carrot breeder with Nunhems/BASF, added to the conference with the keynote address, sharing his experiences, thoughts and observations from 40 years as a commercial carrot breeder.

To illustrate the length of his career, he reminded his audience how much technology has progressed over the course of the last four decades, mentioning the replacement of pay phones with smart phones and the transition from paper to digital data collection and storage.

Looking back on his career, Freeman first experienced carrot breeding in 1976 at Texas A&M University and then later completed his Ph.D. work on carrots at the USDA/University of Wisconsin before starting his career as a commercial carrot breeder in 1982 in Brooks, Oregon.

In his presentation, Freeman covered the history of commercial carrot production in the U.S., starting in the 1940s. This included the transition from open-pollinated varieties to hybrids, and the shift of production concentration from the eastern U.S. into California as the utilization of ice and refrigerated transport allowed for the availability of fresh year-round supply. Speaking to more recent changes, Freeman detailed the development of two new market segments of cut-and-peel snacking carrots and novel colored carrots. During these years, a very significant consolidation took place, through acquisitions, into much larger growers, retailers and global seed suppliers, Freeman recalled. He also spoke about the application of new digital and genetic tools, and the precision and efficiency improvements in farming and seeds.

While sharing experiences and perspectives related to commercial carrot breeding and production during his 40 years in the industry, Freeman also discussed the careers and contributions of three late university carrot researchers. This included the discovery and implementation of cytoplasmic male sterility into orange carrots, followed by the release to seed companies of an inbred line possessing this trait in 1963 by Dr. C.E. Peterson at Michigan State University. It was a very significant discovery and release and now the basis of almost all carrot hybrids used in North America and possibly a majority throughout the world, according to Freeman.

Laura Maupin, a carrot breeder with Bayer, and Diana Londono with Rijk Zwaan discuss carrot seed production during a visit to Precision Seed Company, the first stop on the International Carrot Conference field tour of Central Washington. Skagit Valley Tour

The conference moved from the classroom to the field for day two, beginning with the viewing of a cultivar demonstration at the WSU Northwestern Washington Research and Extension Center. Planted specifically for the conference, the trial consisted of 183 carrot cultivars including commercially available varieties and experimental breeding lines. Unfortunately, the soil at the Mount Vernon research center is a heavy clay soil that is not ideal for carrot production. As a result, some roots were cracked and lacked uniformity in shape.

“Most people were very gracious about it. Some of the breeders said ‘We don’t mind this because it gives us a chance to see how well our varieties do under these kinds of conditions,’” du Toit said. “They consider it a purgatory trial. They put the varieties through purgatory and see how well they perform.”

A stop at Ralph’s Greenhouse demonstrated the difference in soil types. Conference organizers had planted a 58-variety organic carrot cultivar trial at the farm, located in the fertile floodplain of the Skagit River. Grown in sandier soil, the roots looked good.

The afternoon provided a broader look at agriculture in northwestern Washington. Agriculture is the top industry in Skagit County, with more than 90 different crops grown in the county. A visit to Washington Bulb Company provided a glimpse of the Skagit Valley’s flower bulb business. More tulip and daffodil bulbs are produced in Skagit County than in any other county in the U.S. The day wrapped up with a tour of Skagit Valley Farm, where visitors made quick stops in fields of Brussels sprouts, broccoli and specialty potatoes.

Carlos Caceres and Mark Overduin participate in a carrot taste test. Central Washington Tour

Conference attendees were invited to stay a third day to tour the carrot industry in Central Washington. About 25 people took advantage of the opportunity to see the scale of production in the semi-arid growing region.

The tour started at Precision Seed Company near Ephrata. Although the group’s late-August visit came at the end of the carrot seed production cycle, they gained understanding of what it takes to produce carrot seed.

This was followed by a stop at WSU’s bee research facility in Othello, where the group heard a presentation on research related to pollinators.

The tour concluded at Klaustermeyer Farms in Basin City. Harvest was underway, and the grower’s novel method of topping carrots before pulling them from the ground intrigued the group and was an example of the insight participants – from students to breeders – took home with them.

“When you understand the connection of what you do to the actual producer’s situation, it puts the context in place for your work, whether you’re a researcher like me or a breeder,” du Toit says. “You have a more thorough understanding of how carrots are grown, how they’re used and what kind of traits might be important from a breeding perspective.”

Providing learning opportunities through this conference depends on a team effort among researchers, universities, local seed companies and growers, du Toit said, adding that this is what makes the meeting most enjoyable for her.

“It’s that sense of community that everyone is in this together to help support the ability to grow good carrots and a healthy supply of carrots,” du Toit said. “This conference is important for bringing people together to share, to understand better and to move forward as a whole community. That’s why we keep going and why we keep doing this work.”

The 41st International Carrot Conference is planned for spring 2024 in North Carolina.

-

Grimmway Farms CEO Wins Organic Grower of the Year Award

The Organic Produce Network has chosen longtime organic grower Jeff Huckaby as the recipient of the fifth annual Grower of the Year award. Huckaby, president and CEO of Grimmway Farms, was selected based on his ongoing commitment and dedication to excellence in organic production, organic industry leadership and innovation. The Organic Produce Network praised Huckaby for encouraging water conservation and natural methods for pest control, as well as for sharing information about these practices with other organic growers.

Huckaby, a fourth-generation farmer, joined Grimmway Farms in 1998, managed its organic division and became president and CEO in 2016. During his tenure, the program has grown from several hundred to 40,000 acres of certified organic ground.

-

Pop Goes the Weevil

By Mary Ruth McDonald, Tyler Blauel and Kevin Vander Kooi, University of Guelph

The carrot weevil (CW) is an important pest of carrots in Ontario, Canada, especially early in the season. This weevil, Listronotus oregonensis, can cause high levels of crop loss in the high organic matter soils of the Holland Marsh, Ontario, Canada.

The adult CW is active early in the season, even before most carrots are seeded. The adult overwinters in sheltered areas at the edges of fields and walks into the field in early May in Ontario. The weevils begin looking for carrots that are suitable in size to deposit their eggs. Generally, carrot weevils do not feed on carrots, or deposit eggs, until after the first true leaf stage.

The larvae hatch and begin feeding and tunneling through the upper third of the carrot root (Fig. 1). Larval feeding on small carrots, during the fourth to sixth leaf stage, often kills the carrot. Feeding on larger carrots can often go unnoticed until harvest, and this feeding damage renders the carrot unmarketable.

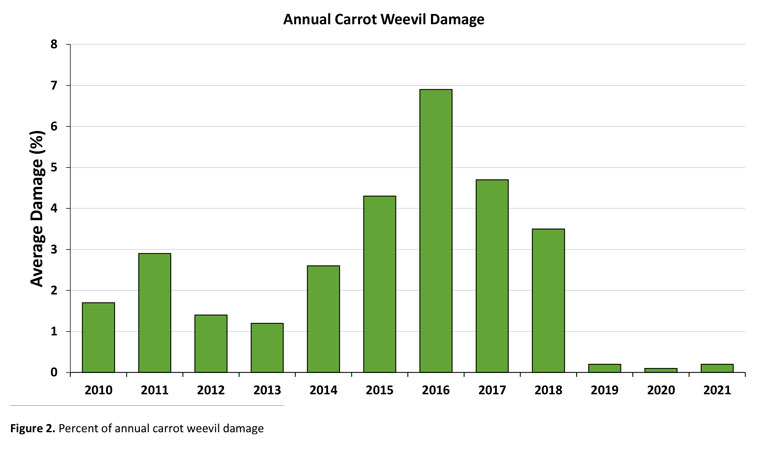

Carrot weevil feeding has caused damage and crop loss in past years in the marsh. In 2016, an average of 7 percent of carrots were lost due to CW (Fig. 2), despite the application of insecticides. Growers were regularly applying Imidan 70-W (a.i. phosmet) for many years, and it is likely that CW was developing resistance, as the product was no longer as effective as it used to be.

A

B

C

Figure 1. Carrot weevils can cause damage and crop loss. Pictured, are (a) a young carrot killed by weevil feeding, (b) an adult feeding, (c) weevil feeding damage, and (d) larva in a carrot root. Research Trials

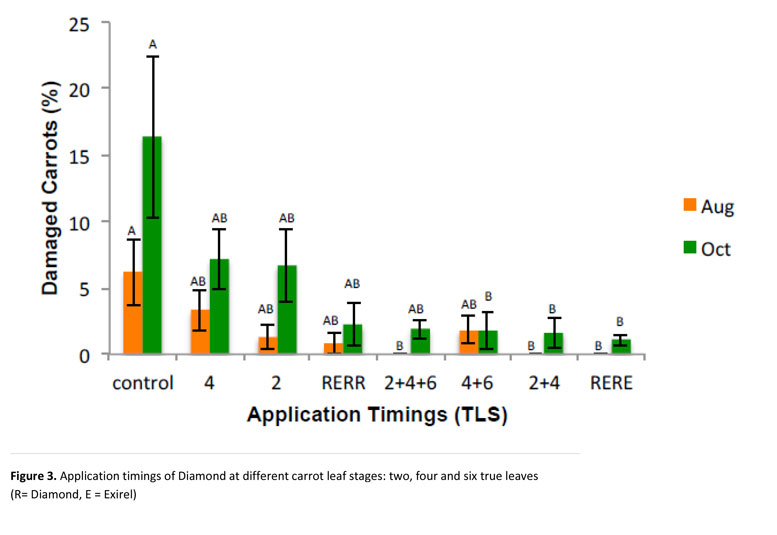

In 2016, research trials at the University of Guelph Ontario Crop Research Centre – Bradford (formerly the Muck Crops Research Station) began testing new insecticides for CW control. The insecticide Diamond (in Canada – Rimon 10 EC; a.i. novaluron) was effective and resulted in lower damage (13 percent) compared to the untreated check (35 percent) and Imidan (27 percent). Further trials testing other insecticides found Exirel (a.i. cyantraniliprole) was also effective in controlling CW with lower overall damage (17 percent).

Once effective products were found, the next question was when to apply these products to obtain the best results. Insecticide timing trials took place in 2018 and 2019 to investigate this. Diamond was applied at different leaf stages, and carrots were evaluated at harvest. Diamond applied at the second leaf stage, and again at the fourth leaf stage in high-pressure fields, was the most effective to minimize damage and maximize yield at harvest compared to the untreated check (Fig. 3).

In addition to effective insecticides and well-timed applications, choice of seeding date can avoid CW damage. Late seeding can avoid a high-pressure window. To test this, seeding date trials were conducted without the use of insecticides. Carrots planted earlier in the season, April to the first half of May, had higher CW damage (82 percent) compared to carrots seeded in late May or later (12 to 40 percent). This makes sense as CW are active earlier in the season and require a developing carrot plant to lay their eggs. Carrots seeded later in the season avoid the main egg laying period and, therefore, often end up with less damage.

Management Recommendations

Scouting and trapping for CW adults is important to know if CW are present in your field, and this starts early in the growing season. Wooden (Boivin) traps (Fig. 4) are set up at the edges of fields before carrots are seeded and are moved into rows after seeding. This trap uses a carrot bait as a lure, and the number of CW found in a field relates to spray thresholds. Generally, if a cumulative 1.5 CW/trap are found, a Diamond or Exirel spray is recommended at the second leaf stage. If the field has over five CW/trap, another spray is recommended at the fourth leaf stage.

Our monitoring of carrot fields, damage and CW egg laying sites has also observed a possible second generation of CW, which we are currently studying to understand more thoroughly.

Successful management of carrot weevil involves scouting, effective insecticides, good spray timing and possibly altering the seeding date. These have decreased the overall CW damage to 0.2 percent, on average.

For more information on carrot weevil management, check out the “How to Control Carrot Weevil” video on the Muck Crops IPM YouTube channel. Details of the trials can be found on the research station website at https://bradford-crops.uoguelph.ca.

-

Estimating the Economic Impact of Bacterial Blight

By Gina Greenway, Greenway Research

One of the most costly and persistent challenges impacting carrot seed production is bacterial blight, caused by Xanthomonas. The economic impact of the disease is particularly frustrating because it ripples through multiple links in the supply chain. At the grower level, management expenses increase the cost of production while losses in yield reduce revenue. Lower yields and higher costs are always concerning, but the sharp increases in agricultural input prices combined with looming drought have created a more pronounced level of risk. At the next link in the supply chain, seed companies incur the high cost of Xanthomonas disinfection practices.

Both growers and seed companies have to reconcile the high investment in the crop against the risk of Xanthomonas impacting seed quality and marketability. As a result, every aspect of bringing the seed to market must be managed intensely but balanced with frugality.

Bacterial blight can infect the flowers of carrot seed crops, potentially reducing yield. Photo courtesy Jeremiah Dung, Oregon State University Methods

Improving understanding of the economic impacts of bacterial blight starts with establishing benchmarks. The initial focus has been to gain insight into the in-field impacts of bacterial blight in direct-seeded hybrid carrot seed crops grown in the Pacific Northwest. To do this, an expert opinion survey of growers and crop consultants in major carrot seed producing regions of Idaho, Oregon and Washington was administered. The goal was to better pinpoint the number of blight-targeted applications typically made per season and to gain a better understanding of the impact of bacterial blight on yield.

To arrive at dollar value estimates of the impacts of bacterial blight, results of the survey were combined with label and price information for bactericides, hybrid carrot seed price and yield estimates, and direct-seeded hybrid carrot seed acreage estimates for the Pacific Northwest.

Bacterial blight can prevent umbel development. Photo courtesy Jeremiah Dung, Oregon State University Results

Survey participants were asked to estimate the number of copper bactericide spray applications typically made per season. About 40 percent of folks who responded reported making two spray applications per season. Another 60 percent of respondents reported typically making three blight-targeted bactericide spray applications per season.

To quantify the impact of bacterial blight on revenue, survey participants were asked to estimate how much yield would increase if bacterial blight did not exist. Responses ranged from 20 percent to 50 percent.

The cost of a typical bactericide application was estimated to range from $20 per acre to $25 per acre but will depend on application rate, price fluctuations and region. Application costs will depend on how the product is applied and whether it is delivered as part of a tank mix or as a dedicated application. This analysis omits application charges.

The number of direct-seeded acres in all major Pacific Northwest regions was estimated to be 5,299, and the price of seed was estimated to range between $9 and $14 per pound. Yields were estimated to range from 350 to 400 pounds of seed per acre.

Industry-wide expenditure on blight-targeted bactericide applications in direct-seeded acreage was estimated to range from $210,000 to $315,000. The estimates are calculated based on the assumption that 90 percent of direct-seeded acres are treated with bactericides.

A field of carrot seed blooms. Estimates of the value of lost yield attributed to bacterial blight will likely be a little bit different every year, for every region, and from farm to farm. It would be difficult to quantify how much yield is lost with a high level of precision, but it is worth considering how much various scenarios of yield loss could cost the industry. If 50 percent of direct-seeded acres are impacted by a 20 percent reduction in yield because of bacterial blight, and the assumed price is $9 per pound, the foregone value rings in at over $1.8 million. If 50 percent of planted acres experience a 35 percent yield loss at an assumed price of $14 per pound, the forgone value would be over $5 million.

Conclusions

Bacterial blight is expensive to manage, negatively impacts valuable yield, and can impact seed quality and marketability. However, there are some promising new mitigation techniques on the horizon that could assist in making management of the disease more proactive and effective.

Author’s note: This work was funded by the United States Department of Agriculture Specialty Crops Research Initiative (grant no. 2020-51181-32154).

-

Blowin’ in the Wind

Insights into Bacterial Blight Epidemiology

By Jeremiah Dung and Jeness Scott, Central Oregon Agricultural Research and Extension Center, Oregon State University

A research study is paving the way for the development of a forecasting model to help growers manage bacterial blight in carrot seed crops.

Figure 1. Bacterial blight symptoms can be seen on carrot flowers and sepals. Bacterial blight of carrot is a common disease and is caused by the plant pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas hortorum pv. Carotae (Xhc). Infection results in irregular, chlorotic areas on leaves, petioles and stems that turn into water-soaked, necrotic lesions and blighted leaves.

The Xhc pathogen can be transmitted by infected seed, and the seed-borne nature of Xhc makes it a major concern for Oregon’s hybrid carrot seed industry. In seed production systems, bacterial blight can result in blighted umbels (Fig. 1), causing reduced seed yield, lower germination rates of harvested seed, and infected seed.

Several species of Xanthomonas, including Xhc, are considered epiphytes, meaning that they can survive and multiply on the leaves, stems, flowers and/or fruits of plants, often without causing symptoms. In the case of Xhc, the bacterial blight pathogen can persist and reproduce on carrot leaves epiphytically and asymptomatically, with disease developing only after large populations are attained on foliage (over 1 million colony-forming units per gram of leaf tissue).

Additionally, many epiphytic bacteria are subject to and dispersed in air currents through various mechanisms. Consequently, carrot seed crop canopies can be potential sources of airborne Xhc in naturally occurring aerosols. Previous studies have collected Xhc in air sampled during carrot seed harvest and combining events, demonstrating the potential for short- and long-distance movement of the pathogen in dusts and aerosols generated during cultural practices.

Field Research

The biennial nature of carrot seed production requires at least 13 months from planting to harvesting, resulting in a potential “green bridge” that facilitates Xhc survival from year to year. Consequently, the crop is potentially exposed to bacterial blight inoculum from the seedling stage until harvest.

We conducted a field study to quantify and characterize the amount and timing of airborne Xhc throughout the carrot seed production season and identify weather factors that contribute to airborne Xhc in and around carrot seed fields.

Hirst-type Burkard seven-day volumetric spore samplers were used to sample air continuously in two carrot seed-to-seed fields which were located approximately 6.4 km apart and intended for harvest in 2019. Air samples were collected from the beginning of stand establishment (August 2018) through November 2018 and from April 2019 through harvest (October 2019). Fields were not sampled from December 2018 through March 2019 due to the inability of accessing and maintaining the spore samplers located at each field site.

Samples from Burkard spore traps were separated into daily segments and DNA was extracted from each sample. The number of Xhc genomes present in each air sample was quantified using a previously published quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay specific to Xhc.

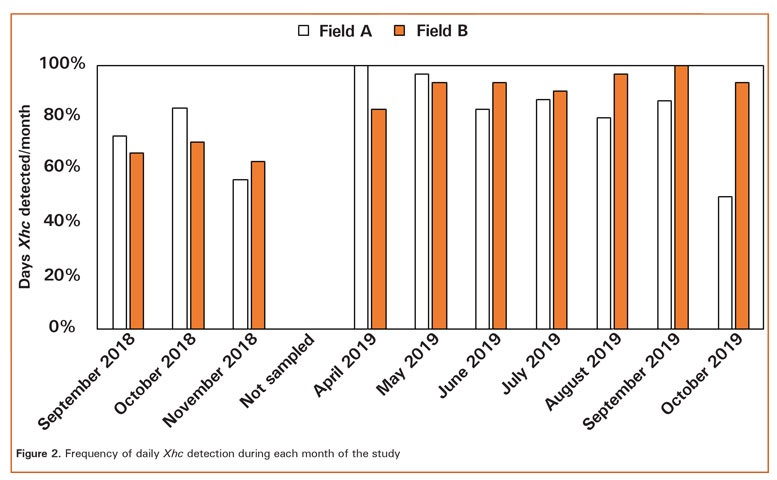

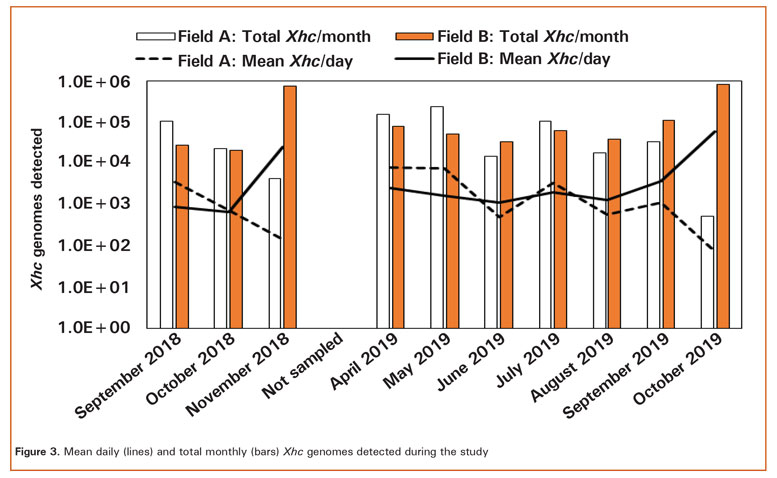

During the 2018-19 season, air samples were collected on a total of 273 and 289 days in two fields, and Xhc was detected on 223 (82 percent) and 245 (85 percent) sampling days (Fig. 2). On average, 2,600 and 7,000 Xhc genomes were detected on a given day, and a maximum of up to 730,000 Xhc genomes were detected on a single day (Fig. 3).

To identify factors most significantly correlated with airborne levels of Xhc, principal component analysis was conducted using weather data collected by the MRSO AgriMet Weather station located at the Central Oregon Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Madras, Oregon. Principal component analysis identified temperature (daily mean, maximum and minimum air and soil temperatures), wind (wind speed, direction and run) and factors related to moisture (daily precipitation, relative humidity and dew point) as being associated with Xhc in air samples.

Growing conditions in the high desert, where carrot seed is frequently produced, are often characterized by sunny and dry days, windy afternoons and cool nights, which may contribute to the dispersal of airborne Xhc in and around carrot seed fields.

This study provides a foundation for the development of a forecasting model to aid in the management of bacterial blight in carrot seed crops. By identifying weather factors and cultural practices that promote the reproduction or dispersal of Xhc, growers can potentially time their bactericide applications to occur prior to the development of favorable conditions or practices, maximizing the protective effect of copper-based bactericides.

Authors’ note: This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, through the Specialty Crops Research Initiative Project grant no. 2020-51181-32154 and the Western Integrated Pest Management Center project ID 1616. Additional funding was also received from the Agricultural Research Foundation.