|

Click to listen to this article

|

By Kylie D. Swisher Grimm, Gina Angelella and W. Rodney Cooper, USDA-ARS

Christopher Gorman, David Crowder and Carrie Wohleb, Washington State University

In the Columbia River Basin region of Washington and Oregon, the phloem-feeding beet leafhopper vectors three pathogens to vegetable and seed crops. Beet curly top virus (BCTV) causes yellowing or slight reddening of leaves, leaf curling or cupping, and plant stunting in crops such as sugar beet, bean, coriander, tomato, pepper and cucurbits. Beet leafhopper-transmitted virescence agent (BLTVA) phytoplasma generally causes purpling of upper leaves and leaf curling in affected crops such as potato, tomato, pepper and carrot. BLTVA also induces aerial tuber formation and early plant senescence in potato and causes the over-proliferation of lateral roots in carrot. Spiroplasma citri can occur in carrot and causes infections characterized by leaf purpling or yellowing, stunting of shoots and taproots, and the over-proliferation of lateral roots. Fields infected with any of these three pathogens can see a reduction in yield and crop quality depending on the severity of infection.

All three pathogens have been found simultaneously in individual beet leafhopper specimens and in tissue from individual plants, highlighting the seriousness of these pathogens in the Columbia River Basin. There are currently no treatments that prevent or manage the pathogens themselves, so growers must manage the beet leafhopper by removing weedy hosts like kochia and wild mustard and by applying insecticides to their crops or the weedy hosts. These management strategies can be costly for a grower.

Information on pathogen distribution among crops, and on seasonal beet leafhopper population dynamics and associated pathogen prevalence, can help growers assess the potential for damage to their crops and aid them in their integrated pest management (IPM) decisions. With funding support from the USDA Office of National Programs Areawide Pest Management Program and the Washington State Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant Program, scientists at the USDA and Washington State University (WSU) have been working to generate this information.

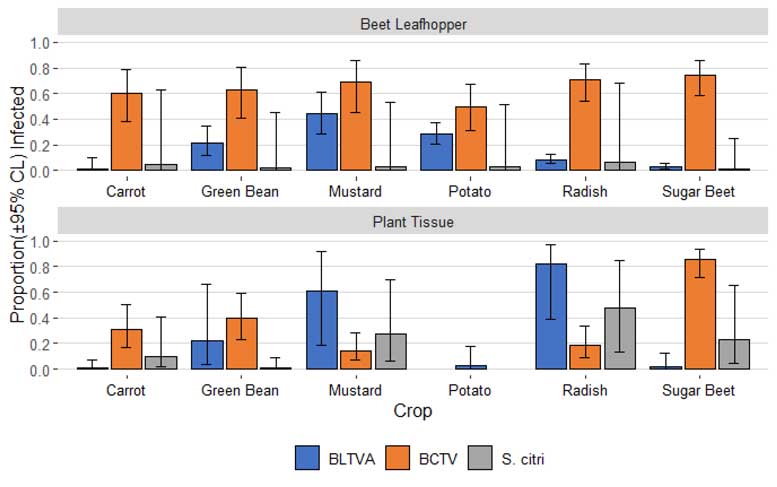

A replicated plot study with six crops (potato, green bean, sugar beet, radish, carrot, mustard) was conducted at the USDA-ARS farm in Moxee, Washington. Beet leafhoppers and plant tissue were collected from each plot on a bi-weekly basis. In beet leafhoppers, BCTV levels were the highest and S. citri levels the lowest among the three pathogens regardless of the crop where specimens were captured (Fig. 1a). BLTVA prevalence varied in beet leafhoppers collected from the different crops. Contrary to this, the levels of all three pathogens varied in plant tissue from the six different crops used in the study (Fig. 1b). These results indicate that pathogen transmission by the beet leafhopper to different plant species may not be equal. This trial will be replicated in 2023 to confirm these findings.

Monitoring the Situation

WSU Extension scientist Carrie Wohleb has been providing insect monitoring data on specimens, including the beet leafhopper, collected from potato fields across the Columbia Basin since 2009. In 2020, vegetable and seed fields were included in the pest monitoring network to increase the coverage of beet leafhopper captures across the region. Since then, the total beet leafhopper population collected in a season has ranged from 24,942 in 2020 (from 45 potato and 24 vegetable/seed fields) to as many as 55,968 in 2021 (from 47 potato and 20 vegetable/seed fields).

Weekly beet leafhopper population results are disseminated to growers and crop consultants via an e-newsletter called WSU Potato Alerts. In collaboration with David Crowder, beet leafhopper monitoring data are interpolated and displayed as geographical contour maps that highlight areas of high to low beet leafhopper densities across the region to help growers with their IPM decisions. This data is displayed each week in WSU Potato Alerts but is also available at www.potatoes.decisionaid.systems.

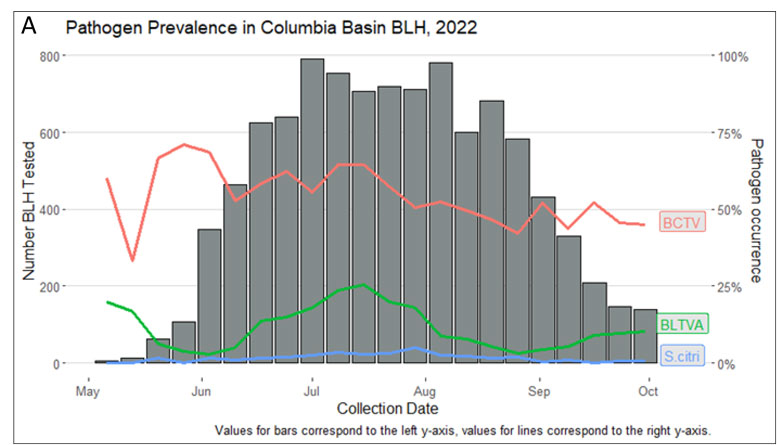

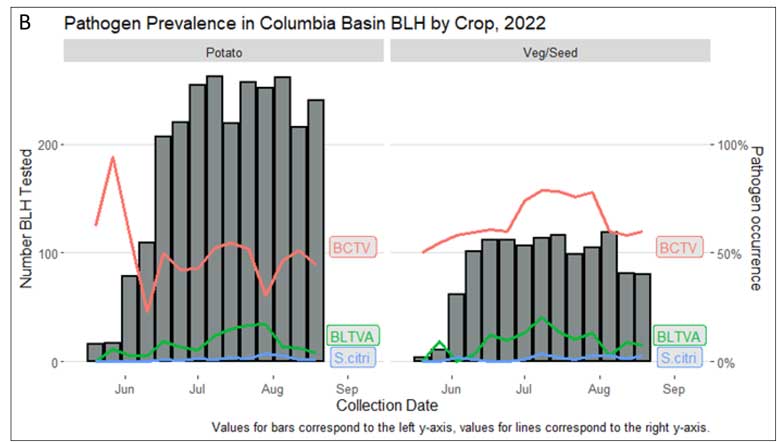

New insect extraction and molecular diagnostic methods were developed and validated in the laboratory to enable the timely processing of insect specimens, so near-weekly pathogen prevalence data could be displayed alongside the beet leafhopper population data in 2022. A total of 33,775 beet leafhoppers were collected from 44 potato fields and seven vegetable or seed fields during the 2022 field season. Results consistently showed high levels of BCTV and low levels of S. citri over the 22-week season (Fig. 2a). Despite having high initial rates of BLTVA when the beet leafhopper population was low, the prevalence of this pathogen peaked at 25.35 percent in mid-July when beet leafhopper population rates were much higher. When pathogen prevalence was assessed by plant host, rates of BCTV were higher from beet leafhoppers collected from vegetable and seed fields as compared to potato (Fig. 2b). This indicates that there could be a previously unknown host-directed beet leafhopper response based on BCTV pathogen prevalence, though further research is needed to confirm this result.

Tracking Trends

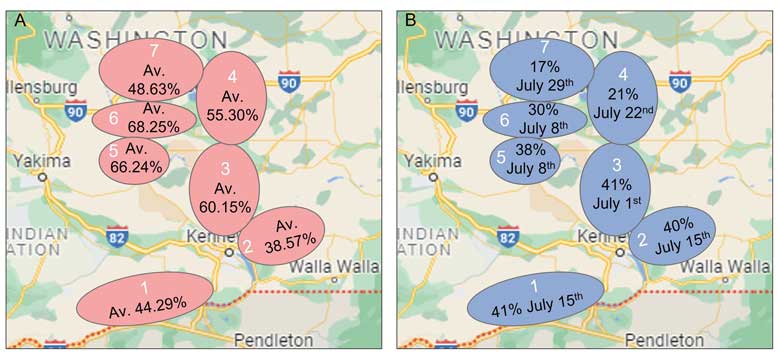

Irrigated agriculture in the Columbia River Basin of Washington encompasses a wide geographic range. The 2022 beet leafhopper collection locations were divided into seven geographically defined regions to assess differences in pathogen prevalence based on geography. Regions were identified as the following: Paterson, Snake River, Basin City, Othello, Mattawa, Royal City and Quincy. Average BCTV pathogen prevalence was lower in the southern Columbia Basin regions of Paterson and Snake River, while average levels were higher in the central regions of Mattawa, Royal City and Basin City (Fig. 3a). Average levels in northern Columbia Basin regions of Othello and Quincy were moderate, despite being the only two regions where traps were deployed in vegetable and seed crops. This suggests that location in the Columbia Basin could have a greater impact on BCTV pathogen prevalence than crop type alone. While BLTVA pathogen prevalence peaked at different weeks in July among the regions, the highest peak rates were at 40-41 percent in early to mid-July in the southern regions, and the lowest peak rates were at 17 and 21 percent later in July in the northern regions (Fig. 3b). Overall, these results suggest that BLTVA could be a higher threat in the lower Columbia Basin and BCTV a higher threat in the central region. Data from additional years is needed to confirm these results and determine if this is a consistent trend or simply a unique finding in the 2022 season.

During the 2022 season, BCTV, BLTVA and S. citri pathogen prevalence in beet leafhoppers was incorporated into the WSU Potato Decision Aid System (www.potatoes.decisionaid.systems). Here, heat maps depict weekly rates of pathogen prevalence broken down by region, and visitors can toggle between the weekly data to observe pathogen changes over time. The goal is to have this information updated weekly throughout each growing season to help growers make more informed IPM decisions regarding timing and number of applications for control of the beet leafhopper. This information, in addition to knowledge gained from field or greenhouse trials that explore pathogen dynamics across different crops and beet leafhopper movement in the landscape, should enable growers to improve management of the economically important beet leafhopper-associated pathogens.